“Imagine a twenty-first century piece of software trying to run on a twentieth-century computer, and you have a fair picture of the New Zealand democratic system”. -Max Rashbrooke

Max Rashbrooke’s upcoming contribution to the Transitional Democracy series is just one of a growing number of calls for urgent reform to our democratic system in Aotearoa, NZ. We are living in a time of transition, and it is clear that whatever comes next, we will need to upgrade how we do democratic governance to navigate the path ahead together. (To find out exactly what we mean by ‘Transition’ and ‘Democracy’, please read this introductory piece.)

Above all, we are in need of a new shared understanding, or ‘grand narrative’ for democracy. So what might a new fit-for-purpose system worthy of the definition of ‘Democracy 2.0’ look like in Aotearoa?

Grounded in the Maori Worldview

Te Ao Māori and Mātauranga Māori ( the Māori worldview and knowledge) must underpin the foundation of any concept of Democracy 2.0 in Aotearoa. The Māori worldview includes principles such as ora, or wellbeing achieved through living in balance with fellow humans as kaitiaki (custodians) of the natural system within a given bioregion. Māori (and arguably tau iwi who adhere to this philosophy also) have an inherent right to live within a system governed by this traditional worldview. However, this fact has been all but ignored by the crown in its vigorous imposition of the colonial system of Western democracy which governs us all currently.

The Māori-led Matike Mai constitutional reform movement seeks to redress this history through a goal of constitutional transformation of Aotearoa by 2040 to reimagine the relationship between the Crown and Māori. The Government could serve us all well by rising to the opportunity to have the difficult, yet essential and rewarding conversations needed to progress this topic.

This tradition of Māori deliberative democracy includes a well established and highly evolved tradition of participatory and deliberative decision-making and collaborative governance of the commons. The fact that Matike Mai was a radical example of citizen-led, mass-scale collaborative democratic activity over a five year period involving over 10,000 adults and children, is clear evidence the Māori tradition of deliberative democracy is alive and well.

This Māori worldview-based system and deliberative democracy tradition offer powerful lessons and models for replacing the democratic systems imported from the West. These imported systems have clearly failed miserably at providing better outcomes for citizens and nature so learning from this wealth of indigenous knowledge and tradition is long overdue in Aotearoa. The Ecuadorian constitution, for example, now incorporates the indigenous concept of Sumak Kawsay (buen vivir or good living) which is similar to ora, and also recognises concepts including the inherent rights to self-governance of indigenous communities and the rights of nature.

Genuinely Participatory

Engagement and consultation are all too often bandied around as buzzwords, but we have all too often been let down by their outcomes. As Rashbrooke says, “our ‘involvement’ often consists of little more than filling out boxes in consultations about decisions that have already been made.” Māori have experienced the emptiness of such words and promises of delegation of real power or decision-making far more acutely than the rest of us.

Truly Participatory Democracy means “a deliberative dialog and decision-making process which hears all voices and diverse perspectives to enact meaningful change.”

There are many innovative ways of ensuring meaningful participation in ways that are easy and lightweight for already busy citizens. For example, liquid democracy allows citizens to vote themselves, or delegate their vote to a trusted person or NGO on an issue by issue basis. Other popular ideas right now are Citizen Juries or Citizens Assemblies which both place randomly selected Citizen representatives in parliament to deliberate on particular issues.

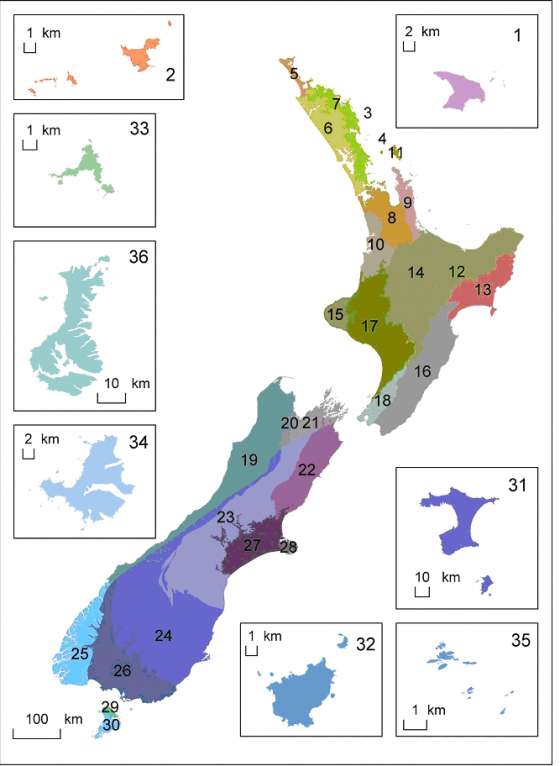

Based on Bioregional Democracy

Another core aspect of Māori, and all indigenous governance systems, is that they are bioregion focused. This approach means that political groupings, decision-making, and governance are based on decisions about how best to live in a balanced state of ora (wellbeing)within the complex system of nature in a particular biological region.

Bioregional democracy has been defined as follows:

“a set of electoral reforms and commodity reforms designed to force the political process in a democracy to better represent concerns about the economy, the body, and environmental concerns (e.g. water quality), toward developmental paths that are locally prioritized and tailored to different areas for their own specific interests of sustainability and durability.”

It is clear that our past approach of ignoring the delicate relationship between people and the unique biophysical features and limits of our local environments has not led to good environmental outcomes in Aotearoa. However, progress on this front is being made. The recently released Biodiversity strategy and Whaitua (catchment) Committees for water governance in the Wellington Region both incorporate a bioregional framework. The restoration of self-governance of Te Urewera National park to the Iwi is a similarly pioneering development in this country.

Truly Decentralised

The Principle of Subsidiarity holds that decisions should default to the most immediate (local) level meaning wherever feasible, so that local people and locally elected representatives have maximum autonomy over matters in their area. This decentralised approach aligns with the principle of bioregional democracy outlined above.

The concept of subsidiarity was codified in the recently rewritten Italian constitution, and has led to far more delegation of powers to regional authorities. It even enables (through the Bologna Declaration) public administrations to support citizens in the development of autonomous initiatives aimed at the collective interest such as community managed services and infrastructure.

This means Public Administrations must “find ways to share their powers and cooperate with single or associated citizens willing to exercise their constitutional right to carry out activities of general interest.” Incorporating this principle in New Zealand would ensure that our cities see Citizens as a “great source of energy, talents, resources, capabilities, skills and ideas that may be harnessed to improve the quality of life of a community or help contribute to its survival.”

India

India United States of America

United States of America New Zealand

New Zealand